Column from November 2, 1999

Attitudes about Disability Prove Almost Lethal

Copyright 1999 by Laura Hershey

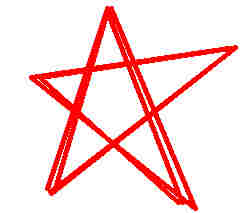

A red star, scrawled in hasty magic marker, screamed a coded message beside my friend's name and patient number, at the door of her hospital room. "What's that red star mean?" I asked a nurse, afraid of the answer I suspected. "That's the DNR" - her offhanded answer confirmed my fear.

I'd already heard about the "do not resuscitate" order earlier that

day. A fellow advocate, a mutual friend of Ginny's and mine, had

talked to a nurse who divulged more than she probably should

have: When admitted to the hospital with pneumonia two weeks

ago, Ginny had acceded to the DNR -- but only after having been

"counseled" by a doctor for over an hour.

friend of Ginny's and mine, had

talked to a nurse who divulged more than she probably should

have: When admitted to the hospital with pneumonia two weeks

ago, Ginny had acceded to the DNR -- but only after having been

"counseled" by a doctor for over an hour.

This news had shocked and horrified me. I know Ginny too well to think she'd "go gentle into that good night." She's more the "Rage, rage against the dying of the light" sort -- a feisty fighter, an outspoken advocate for the rights of people with disabilities and homeless people. Everywhere she goes, she carries full-text copies of the Americans with Disabilities Act and other useful documents on the back of her power wheelchair. And she's not afraid to whip them out and use them when anyone messes with her, or with people for whom she advocates as a volunteer.

That's when she's healthy, of course - or at least healthier. Her physical disability and recurrent health problems don't usually slow her down much. But this pneumonia was really kicking her butt. I could see that now, as I maneuvered my power wheelchair around her hospital bed to get to the side where she could look at me and mouth silent words. A tracheotomy sent oxygen and misted medicine into her lungs, but blocked her efforts to produce any vocal sound. I had to struggle to read her lips. The difficulty of doing this frustrated and discomfited me. I imagined others reacting the same way, and I couldn't help wondering whether that would become, at some point, a factor in assessing her competence, her prognosis, and her "quality of life." Those three medical concepts - subjective concepts wrapped in objective, clinical language - ring alarm bells for me, and for others with disabilities who've faced the assumptions and stereotypes the medical profession holds about us.

After wriggling my chair past machines, a washstand, and other hospital-room obstacles, I greeted Ginny with some words of encouragement. Then, sensing (rightly as it turns out) that we hadn't much time, I went right to the point. I asked her about the DNR -- did she want it? Our friend Becky was there too, leaning over the bed and holding Ginny's hand. With much effort, Ginny seemed to be saying no, she didn't want the DNR order in place.

A doctor entered, on his rounds. He began asking Ginny some questions. How was she feeling? Did the respiratory therapy treatments seem to help? When it seemed he was about to wrap things up and leave, Becky and I both jumped in to tell him that Ginny wanted to talk to him about the DNR, that we thought she wants it revoked.

For the next fifteen minutes, the four of us engaged in a conversation that was difficult, both mechanically and emotionally. Through a painstaking exchange of yes-no questions, nods, scratchy notes, and lip-reading, Ginny conveyed her desire for every effort to save her life.

The doctor heard this message, was willing to hear it; but his obvious biases made him subtly resistant. Here's how he posed one question to Ginny: "Would you want to be put on a respirator?" Ginny responded with a fearful, uncertain look. I instantly insisted on rephrasing the question like this: "If you couldn't breathe on your own, would you want them to use a respirator to save your life, rather than letting you die?" Still with an apprehensive expression, Ginny nevertheless nodded, yes.

By the end of the conversation, Ginny had indicated unequivocally that she would want ventilation if necessary to save her life; and that she would want attempts made to start her heart if it stopped beating. The doctor agreed to remove the DNR order immediately.

After the doctor left, Ginny's mother and sister arrived. Ginny conveyed that she wanted us to tell them about the conversation with the doctor. We did, and they had an immediate, negative reaction. "That's her family's decision," said Ginny's mother. Obviously Ginny's mother and sister saw us, her friends and colleagues in advocacy, as meddling outsiders. Their chilly silence followed us out the door.

That was about a month ago. A lot has changed since then, mostly for the better. Ginny regained her voice, and began growing stronger once the infection left her lungs. She has repeatedly stated her intention to go on living, in front of a variety of witnesses. Her friends have stayed in touch with her, and her situation.

About three weeks after my visit with her, I heard that Ginny's gradual recovery was abruptly interrupted when she went into respiratory failure. Emergency measures saved her life, and her recovery now continues.

Most encouraging, Ginny's mother and sister are now her allies in medical advocacy. They finally saw Ginny's life directly jeopardized, a situation where inaction would have meant certain death. They saw her revived; and they saw that she is still Ginny, not the "vegetable" predicted by doctors. They have helped to ensure that the DNR order has not been reinstated.

Now Ginny's friends feel victorious, but only precariously so. As long as Ginny remains weak enough and ill enough to have to rely on health care systems, she'll be at risk.

Ginny's recent experiences echoed, amplified some of my own encounters with medical professionals who implicitly questioned my viability, or my quality of life. My experience as her friend and advocate verified some of the knowledge I've gained as a disabled woman, and as a disability-rights activist working against the legalization of physician-assisted suicide.

I can already hear some readers' reaction: What does that situation have to do with assisted suicide? Plenty, from my point of view. I believe that the pressure my friend endured, the suggestion that she just give up and die, save herself and everyone else the trouble of her existence, was based on prejudice against her as a disabled woman. And I believe that pressure was nothing compared to the pressure we'll face to allow doctors to end our lives, should that practice ever become legal throughout the United States.

Two things struck me most about Ginny's predicament:

First, I think that DNR order - how it was initiated, and how much effort it took to get it revoked -- offers a clear example of discrimination based on disability. From my own experience, and other people with disabilities', I believe such discrimination is rampant throughout the health care system. Everyone who is admitted to a hospital is asked whether they have a living will; but nondisabled people suffering from acute illnesses like pneumonia are not so strenuously urged to have a DNR in place. It's assumed that they are in the hospital because they want to get better. People with disabilities too often get the subtle or not-so-subtle message that they'd be better off dead. There's a double standard that equals discrimination.

Second, the attitudes displayed by some doctors and nurses, and by Ginny's own family were not vicious or rancorous, nor particularly unusual. They were the kinds of feelings many people hold toward disability: sorrow, pity, discomfort, a little dread. This was not how Ginny felt about her own disability, nor how I feel about mine, though we both encounter these attitudes from others on a daily basis.

And yet these very commonplace, one might say kindly feelings can be lethal to those of us who have disabilities.